This malaise and the fatigue of late summer—how to know its fat underside?

I am in a thing.

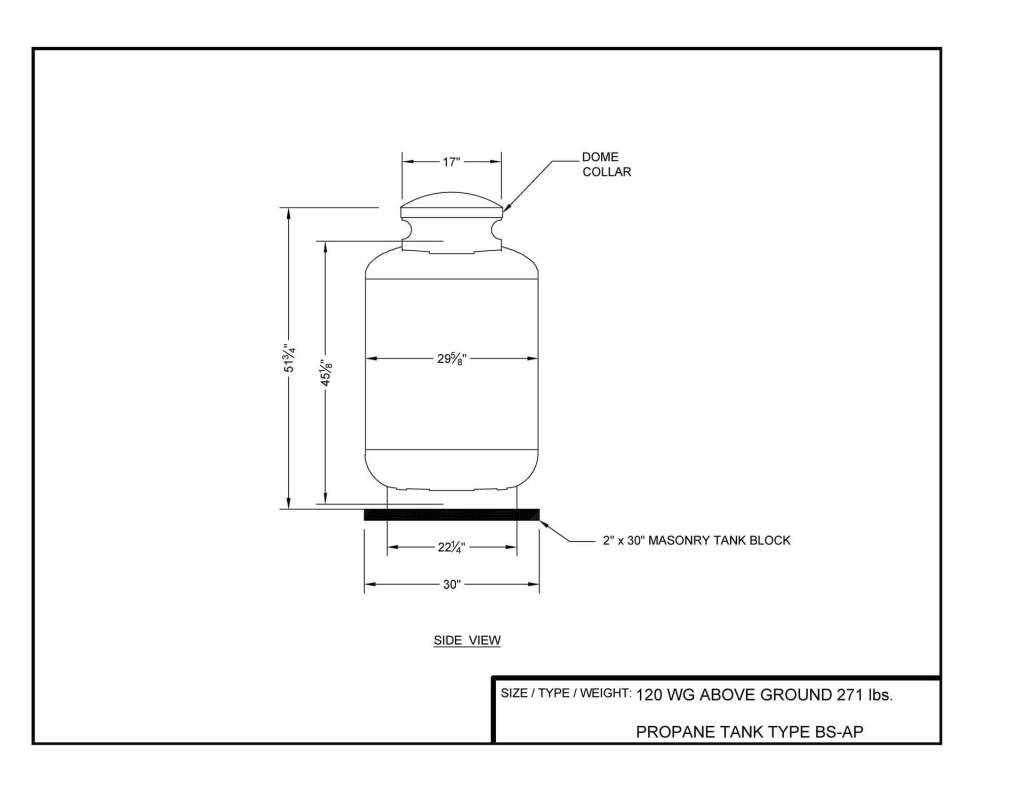

Worse: I make nothing of it. The picture of this thing changes: it is running through fleshy stalks of sweet corn, arms outstretched as if to gather thin cuts from their leaves, and then it is a deer skull on top of a blue cage filled with propane tanks. The versos and rectos remain unmarked. No change in the shape of my spine or the length of my arms confirms how ugly I am become to myself.

What the writing might be is not clear. What the words are to do is not clear.

The trailer park fundamentalists and the Messianic crew who took over the Pic-a-Flick Video and Tanning Salon share their demands. Shared, too, by the farmers out all night shaking the cherry trees: give of your body. Give of your self.

I have given but am no George and have not churned the soil or fed it blood in any real way—that is what there is left to do.

I thought it was self-protection but here in the dark it seems I am not to emerge transformed, transcendent, irradiated and coughing up the dark viscera of my useless, previous interior.

_______

Too much in a mode, isn’t it? So morose and so convinced of its own intelligence—as if performing seeking in writing is the same as actually seeking and then writing. I do know that I hoped, this year, to convince myself that language is a sacred property, and I almost got there. Language, the phenomenon, yes, but how boringly anthropological. What about my mother-tongue, what about English? A language whose rules I barely understand, whose alleys I only half-frequent, whose creoles and colloquialisms seem too exuberant or too limited. Too beyond me.

Plain. Old. English. Nothing interests me in expending creative energy on its scaffolding, the periods and commas and question marks, its stupid-looking exclamation point.

Here, I grow tired of myself—

_______

Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up. Shut the fuck up.

_______

The ground of my poetics is repetition. Lines, rhymes, the process of writing. Lines. Rhymes. The process of writing. Is it a process? In the sense of a procession: the poems I make march past me (last I was in a parade I rode in a roll-off box and threw Tootsie Rolls to kids. I really beamed one boy I loved—how else to let him know?), and not in the sense of the routine brutality of the processing plant, the mechanical separation of animals into their parts. Let poetry not be slaughter.

Maybe vivisection.

The work I have to do has something to do with all of us but I am aching under the weight of the question. The one word, the why. So the work becomes the repetition of the question, and its answers: To give it into our mutual holding.

Why? To make America act decently at least once in my lifetime.

Why? To insist that soft misogyny was only the grounds of our bonding, and then recant that position. To hurt out loud in a voice you might recognize.

Why?

_______

I wrote in a poem, ‘I fled the devil,’ but I might have said, ‘I, the devil, fled’ with as much conviction. There is a pushing against the self to make room for another presence. It might be called Voice but isn’t only that. It is an immediate but temporary grafting of what is deepest in you into the branches of all the rest of it, all that isn’t you, by which you are changed. The threshold, Wordsworth says, is ‘. . . overpast’:

A weight of ages did at once descend

Upon my heart; no thought embodied, no

Distinct remembrances, but weight and power,—

Power growing under weight: alas! I feel

That I am trifling: ‘twas a moment’s pause—

All that took place within me came and went

As in a moment [. . .]

The work of chiasmus in creating a rocking motion, a dialectical pattern that realizes the synthesis it moves towards. The repetitions with a difference, the stations of experience.

_______

I forget the name of the poem by Ellen Bryant Voigt whose first line in full is, ‘The dead just won’t shut up. Already [. . .].’ But I recall that the images that make the dead a presence are woefully plain: a field turned for planting, a bee on a window screen bringing its legs to its mandibles. Here, the repetition is the quotidian experience of the quotidian world. If the dead are in the turned field, are the bees, are in the closet, we will repeat forever our encounters with them. A weight of ages.

Just shut up already.

_______

The last time I heard n———r was Christmas 2017 at my grandparents’ house. A shade of lipstick seemed too dark for an uncle. The last time I was in a friend group that blamed n———rs for our problems—no one to fuck us—was in high school.

The first time I recall hearing the word: Well: my aunt would watch my brother and me when Ma was on third shift. That meant, in the summer, we’d wake up in North Rose, a town named after the town of Rose, which was named after a slaveholding man who had built for himself a mansion near Seneca Lake. He’d brought a handful of slaves up from Georgia.

My cousins and my brother and I are outside, tossing a football back and forth. It’s early, not yet too hot or muggy. A kid is pedaling a little one-speed bike up the street, kicking up dust at the edge of the road. He’s in a grimy-looking grey tank top and cut-off jean shorts. His hair is grimy, his bike is shit. Everything about him says he’s scum. That’s the typology out here. In descending order of importance: Prep, jock, scum. The rest of us are nobodies, I guess. He comes rolling up.

Dust and pebbles spitting from the back wheel.

He comes to a stop next to the side yard where we’re playing and looks at us. He speaks only to my brother and I: ‘Why are you guys playing with them n———rs? N———rlovers? You n———rlovers?” I am eight, which means my brother is seven, and cousin Samantha is nine, and cousin Justin must be twelve or thirteen. Now the kid is just screaming it over and over:

N———rlovers! N———rlovers! N———rlovers! N———rlovers!

My uncle is a big man. Even staying over we hardly ever saw him. Like all my people, he drives trucks for someone. But he is also trying to get into firewood, and spends time after work harvesting at a lot by himself. Won’t pay anyone to help. He is a big, big man. His screen door blasts open and knocks against the wall on the screened porch, the spring screeches pulling it shut behind him, doorframe slapping against the house—a gun-like report.

He runs straight out to the street before the kid has time to turn his shitty little bike around, and the kid is up in the air, held by the front of his shirt, and the kid is crying and my uncle is yelling at him to stay away from his property and his kids, and the kid is begging to be let down, but is angry, too, and when he’s dropped into the dirt on the side of the street, just outside the shade of the black walnut shade trees in the side yard, he sits up and says through his tears, ‘My dad will sue you for fifty dollars!’ and grabs his bike and pedals off, back to whatever hell he lives in.

I feel pride, and fear, and small awakening to the fact of some unalterable difference between my cousins and myself that means part of their life is untranslatable, un-transferrable, incomprehensible to me.

I cannot know those I love, those I have harmed, not knowing.

A weight of ages does descend upon my heart.

2 responses to “Maybe Vivisection”

A privilege to experience this. I feel the ache gave it breath. I admire it.

I love it and can feel it also!